Glial cell tumours called ependymomas typically develop in the lining cells of the ventricular system, with less frequency occurring outside the central nervous system (CNS) or in the brain parenchyma. They are more common in...

What is Ependymoma?

Glial cell tumours called ependymomas typically develop in the lining cells of the ventricular system, with less frequency occurring outside the central nervous system (CNS) or in the brain parenchyma. They are more common in youngsters than in adults and consist of genetically different subgroups of tumours. The management of ependymomas is reviewed in this activity, which also emphasises the importance of the inter-professional team.

Glial cell tumours called ependymomas typically develop in the lining cells of the ventricular system, with less frequency occurring outside the central nervous system (CNS) or in the brain parenchyma. They are more common in youngsters than in adults and consist of genetically different subgroups of tumours.

Etiology

Even while ependymomas that develop in various parts of the CNS are histologically similar, their clinical behaviour frequently varies. Accordingly, ependymomas with identical histological grades may have very diverse clinical outcomes even when they have similar histological grades. Retrospective investigations have shown that histological grading alone has not consistently and reliably predicted survival outcomes. Recent research suggests that these tumours may be divided into separate progenitor cell populations, which would explain why tumours of the same histological grade might have diverse clinical outcomes.

Large genomic areas are affected by number of genetic disorders that have been identified to be associated with ependymoma According to several of these investigations, ependymomas are associated with specific carcinogenic substances and molecular subgroups that may be more reliably associated with clinical outcomes than just histologic classification.

Epidemiology

All age groups are affected by ependymomas, but children are more frequently affected. It ranks as the third most typical brain tumour in young people.

According to the Statistical Report for CNS tumours from the years 2011 to 2015 from the Central Brain Tumour Registry of the United States (CBTRUS), ependymal tumours account for 1.7% of all brain and CNS tumours and have a median age of 44 years.

The most common solid tumour-related cause of mortality in children is brain tumours. The medulloblastoma, pilocytic astrocytoma, brainstem glioma, and ependymoma are the most frequent paediatric brain tumours.

Pathophysiology

The following categories apply to ependymomas based on genetic mutations and variations:

Fossa posterior (PF):

- PF-EPN-SE (subependymoma)

- PF-EPN-B (group B)

- PF-EPN-A (group A)

Supreme Tribunal (ST)

- ST-EPN-SE (subependymoma)

- ST-EPN-YAP1 (YAP1 fusions)

- ST-EPN-RELA (RELA fusions)

Ependymomas of the spine:

- SP-EPN-MPE (myxopapillary)

- SP-EPN-SE (subependymoma)

- SP-EPN

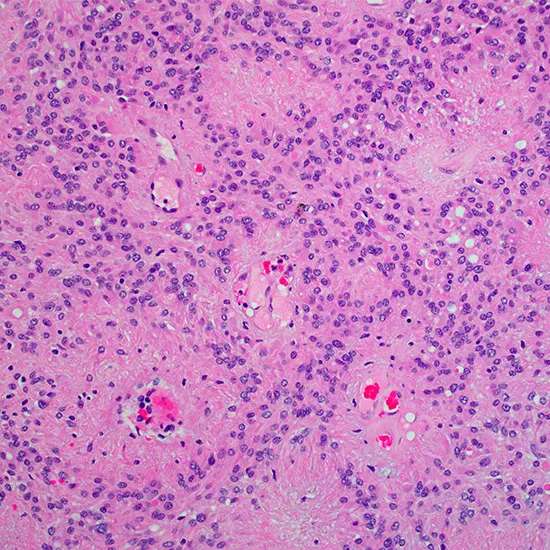

Histopathology

Since ependymomas seldom spread outside of the CNS, the TNM system of categorisation does not apply to them, and instead, the WHO classification for

CNS tumours is currently used to categorise these ependymomas:

- Subependymomas and myxopapillary ependymomas are examples of grade I, slow-growing tumours that are frequently regarded as benign. Subependymomas usually develop in the ventricular walls, most frequently in the fourth or lateral ventricles. Histologically, they are distinguished by a tissue that is hypo-cellular and contains clusters of cells with a bland nucleus encircled by glial matrix. The caudal equina, filum terminal, and conus medullaris are the three areas where myxopapillary ependymomas most frequently develop. Histologically, these tumours seem like pseudo-papillary formations with mucin-rich micro-cysts and cuboidal, radially organised cells surrounding a myxoid stroma.

- Ependymomas of grade II have a high level of cellularity and papillary features. Cells display a transparent cytoplasm and are consistently organised.

- Anaplastic ependymomas of grade III exhibit an abundance of mitotic cells and pseudopalisading necrosis.

Symptoms

- The clinical course of ependymomas can range from an early onset of elevated intracranial pressure producing nausea and vomiting to a more chronic and gradual clinical course as they develop inside various CNS compartments.

- Ependymoma is a histological diagnosis that most frequently manifests in the spinal cord, infratentorial region, and supratentorial region.

- Ependymoma is frequently suspected in adult patients with protracted clinical histories who have an intraventricular lesion on brain imaging that is non-enhancing and clearly defined, isodense on computed tomography, and isointense on T1 images on magnetic resonance imaging. (MRI).

Examination

Ependymomas have historically been categorised using the WHO criteria for classifying nervous system tumours. Predictions of the clinical and biological behaviour of central nerve tumours are frequently made using this histological grade. However, rather than relying just on histology grade, molecular and genetic profiles may offer more precise information in ependymoma.[10]

The WHO classification system for nervous system tumours bases tumour grading on various histological grades; nevertheless, this classification by itself frequently cannot accurately predict the clinical course in ependymoma patients. The 2016 WHO classification for nervous system tumours now includes the presence or absence of genetic changes, RELA fusion-positive or negative, for ependymomas due to growing knowledge of molecular pathogenetic pathways in ependymomas.

In ependymomas, nine molecular groupings have been identified, and they are associated with various anatomical sites, genetic variations, and demographic traits. Based on their molecular subgroup, these new discoveries present the possibility of possibly improving the classification, management, and prognosis information for ependymomas.

Currently, there are no molecular or immunohistochemical markers that are regularly used in the diagnosis process for ependymoma patients.

Treatment/Management

According to the most recent CBTRUS data report, epidermal tumours are extremely uncommon, making about 1.7% of all brain tumours. This makes determining the best management for these entities difficult. Retrospective studies have shown that individuals receiving resection with adjuvant radiation therapy have an increased survival rate. Chemotherapy for adult ependymomas is supported by scant and scant evidence.

The molecular subgroups are not used as recognised recommendations to direct ependymoma treatment. However, the current consensus advises individuals with PF-EPN-A positive ependymoma who are older than 12 months of age to get local irradiation in addition to the maximum safe micro-neurosurgical excision.

The mainstay of treatment for intracranial ependymomas is often surgery. Partial resection has shown worse clinical outcomes and overall survival than complete resection without residual disease.

Treatment options for ependymomas include:

- ependymoma removal surgery

Neurosurgeons want to remove as much of the ependymoma as is practical. Although it is ideal to remove the entire tumour, there are instances where doing so would be too dangerous due to the ependymoma's proximity to delicate brain or spinal tissue. Your child might not need any further treatment if the surgeon is able to remove the entire tumour during surgery. The neurosurgeon may advise a further procedure to try to remove the remaining tumour if some of it is still there. For more aggressive tumours or in cases when the entire tumour cannot be removed, other therapies, such as radiation therapy, may be advised.

- radiation treatment

High-energy beams, such X-rays, or protons, are used in radiation therapy to kill cancer cells. Your kid will experience radiation therapy. After surgery, radiation therapy could be advised to assist prevent the recurrence of more aggressive tumours or if neurosurgeons weren't able to completely remove the tumour. Utilising specialised methods can ensure that the radiation therapy targets the tumour cells while sparing as much of the surrounding healthy tissue as feasible. Radiation therapy techniques including conformal radiation therapy, intensity-modulated radiation therapy, and proton therapy enable medical professionals to deliver radiation with care and accuracy.

- Radio-surgery

Stereotactic radiosurgery, which is technically a form of radiation rather than an operation, concentrates several radiation beams on specific locations to destroy the tumour cells. When an ependymoma returns after surgery and radiation, radio-surgery may be employed.

- Chemotherapy

Drugs are used in chemotherapy to kill cancer cells. For the majority of ependymoma instances, chemotherapy is not very successful. Chemotherapy is still primarily experimental and only used in specific circumstances, such as when the tumour returns after radiation and surgery.

- Scientific tests. Studies of novel medicines are called clinical trials. Although the danger of adverse effects may not be recognised, these trials provide you the opportunity to try the most recent therapeutic alternatives. Consult your doctor to find out if your kid might be able to take part in a research trial.

Diagnosis

Astrocytoma, medulloblastoma, and tumours of the choroid plexus are among the possible diagnoses for tumours in the posterior fossa.

Glial tumors, choroid plexus carcinoma or papilloma, and embryonal tumours are included in the differential diagnosis for supratentorial tumours.

The following tests and procedures are used to identify ependymomas:

- neurologic examination:

Your doctor will inquire about your child's signs and symptoms during a neurological examination. He or she might assess your child's reflexes, balance, strength, coordination, vision, and hearing. Problems in one or more of these areas could reveal information about the region of your child's brain that a brain tumour might be affecting.

- image-based tests:

Doctors can use imaging studies to pinpoint the exact position and size of the brain tumour. Brain tumours are frequently diagnosed with MRI, which may also be combined with specialised MRI imaging techniques like magnetic resonance angiography.

- Cerebrospinal fluid removal for testing (lumbar puncture).

In this technique, which is also known as a spinal tap, a needle is inserted between two lower spine bones to drain fluid from surrounding the spinal cord. To check for tumour cells or other anomalies, the fluid is examined.

The doctor may suspect ependymoma based on your child's test findings and advise surgery to remove the tumour. The tumour cells will be taken out and analysed in a lab to confirm the diagnosis. The sorts of cells and their level of aggression are identified using specialised testing, which the doctor may use to inform therapy choices.

Summary

The most dependable and constant independent prognostic factor for cerebral ependymomas has been the degree of surgical resection. Intracranial ependymomas primarily exhibit a locally invasive histological appearance and exhibit a limited metastatic potential. Ependymomas classified by the WHO as histological grade III have a worse prognosis than those classified as grade II.

When compared to patients who only receive partial resection, patients who receive complete resection without any evidence of residual disease were shown to have a superior prognosis and overall survival. For this reason, vigorous surgical excision is usually the preferred form of treatment.

Infratentorial ependymomas often have a good prognosis, even without therapy, across the various subtypes. Contrary to popular belief, supratentorial ependymomas frequently have a higher histological grade and have a poorer survival rate despite resection and adjuvant radiation therapy.

Paediatric patients' prognoses differ depending on the location, type of treatment, and pathological classification. Gross complete resection had the best overall and progression-free survival, according to a previous study. Patients with WHO classification grade II had increased progression-free survival following gross total resection alone, as well as improved overall survival after gross complete resection combined with external beam radiation therapy. After subtotal resection in addition to external beam radiation therapy, patients with WHO classification grade III experienced an improvement in overall survival.

While individuals with infratentorial tumours who underwent subtotal resection in addition to external beam radiation therapy had a superior progression-free survival rate.

Complications

Long-term CNS tumour survivors may experience a wide range of consequences, including as secondary cancers, endocrine and growth abnormalities, sensorineural hearing loss, neurological deficits, and cognitive limitations. Long-term consequences in adult patients are possible; the most common ones include weariness, tingling and numbness, discomfort, and sleep disturbances.

Patient education

Patients should get prognosis-related counselling. Palliative care helps those with CNS tumours who are towards the end of their lives. Early and proactive counselling will be helpful for patients and their families, in addition to comfort measures. To address the diverse range of requirements that these patients will have, palliative care should be interdisciplinary.

Enhancing health care outcomes

An inter-professional strategy that may involve surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy is the cornerstone of ependymoma treatment. Neurosurgery must be consulted to confirm the tumour through tissue biopsy or tumour excision therapy. Patients who are nearing the end of their lives may require palliative care. Surgery patients may potentially experience a variety of neurological impairments. These people might benefit from occupational, speech, and physical therapy. The neurological impairments are frequently long-lasting.