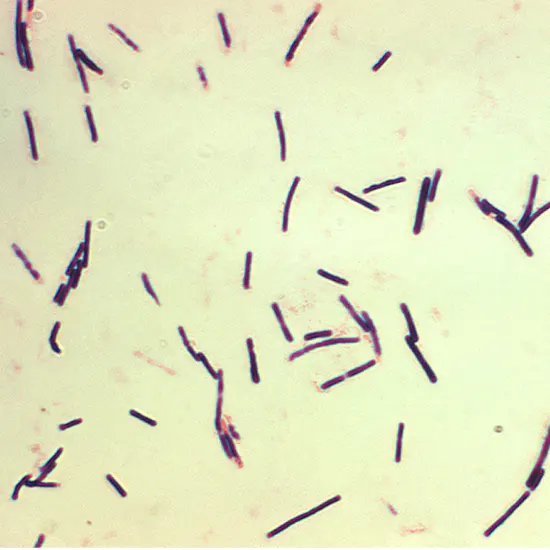

Anaerobic Gram-positive spore-forming bacterium Clostridium perfringens is linked to acute gastrointestinal infections in people that range in severity from diarrhoea to necrotising enterocolitis and myonecrosis.

Anaerobic Gram-positive spore-forming bacterium Clostridium perfringens is linked to acute gastrointestinal infections in people that range in severity from diarrhoea to necrotising enterocolitis and myonecrosis. This pathogen may produce spores that are resistant to environmental stress and has a wide variety of toxins involved in the pathogenesis of illness.

Spores of C. perfringens can endure standard cooking temperatures. As a result, it can grow in foods that have been stored incorrectly. The most frequent causes of outbreaks are incorrectly prepared or reheated meats, poultry, or gravy. The inter-professional team members involved in the management of gram stain patients with Clostridium perfringens infections would benefit greatly from this exercise, which will highlight the epidemiology, pathophysiology, and other important elements.

Anaerobic gram-positive spore-forming bacterium Clostridium perfringens is linked to acute gastrointestinal infections in people that range in severity from diarrhoea to necrotising enterocolitis and myonecrosis. This pathogen may produce spores that are resistant to environmental stress and has a wide variety of toxins involved in the pathogenesis of illness.

Etiology

After an autopsy on a 38-year-old man, William H. Welch, MD, originally identified Clostridium perfringens in 1891 at The Johns Hopkins Hospital under the name Bacillus aerogenes capsulated. Bacillus welchii was its previous name, which was later changed to Clostridium perfringens, which is Latin for "burst through."

Alpha-toxin (CPA), beta-toxin (CPB), epsilon-toxin (ETX), iota-toxin (ITX), enterotoxin (CPE), and necrotic enteritis B-like toxin (NetB) production is used to classify organisms.

A: Only CPA

A: CPA, CPB, ETX B: CPA, CPB, CPE (plus/minus)

D: CPE (+/-), ETX, and CPA

E: CPE (+/-), ITX, and CPA

CPA and CPE

G: NetB, CPA

Spores of C. perfringens can endure standard cooking temperatures. As a result, it can grow in foods that have been stored incorrectly.

Epidemiology

There is evidence that type A and type C poisons can harm humans. Most cases of non-food-borne diarrheas illness and food poisoning linked to C. perfringens are caused by type A. 5% of outbreaks, 10% of illnesses, and 4% of hospitalisations are attributed to C. perfringens, according to CDC epidemiology surveillance data for food-borne disease outbreaks. With a median outbreak-associated disease number of nearly 1,200, the annual median epidemic size was 24. The majority of instances appear between the ages of 20 and 49, with a slightly greater prevalence in men (65%), according to the data. Undercooked beef is the most typical vehicle for transmission, followed by poultry. There were outbreaks throughout the year, with November and December having the highest occurrence.

In post-World War II Germany from 1944 to 1949 and in the Highlands of Papua New Guinea, referred to as Darmbrand and Pinball, respectively, Type C has been linked to endemic enteritis necroticans.Severe malnutrition is thought to make people more vulnerable to type C infection. Pigbel was noted as the leading cause of death in children over 1 year old between the 1960s and 1970s. A vaccine drive in the 1980s assisted in lowering the prevalence, although the illness still results in significant morbidity and mortality.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of C. perfringens is caused by tissue necrosis caused by the toxin. The majority of toxins have pores that open up, allowing water and solute to flood in and cause swelling and cell death. The fermentation of glucose results in the generation of histotoxic gas, which is a defining feature of C. perfringens infection.

The poisons that C. perfringens produces are

CPA is an enzyme that can degrade sphingomyelin and phosphatidylcholine on cell membranes, stop neutrophils from migrating and maturing, and trigger the metabolism of arachidonic acid, which causes vasoconstriction and platelet aggregation. As a result, this toxin produces a microenvironment with poor tissue circulation and innate immune response impairment.

Through the release of substance P, the pore-forming toxin CPB is known to bind endothelial cells and have neurotoxic effects. Furthermore. It has been demonstrated that the toxin is crucial to the pathogenesis of necrotising enterocolitis.

CPE is a toxin that creates pores by attaching to claudin receptors on the cell surface and creating a hexamer complex that permits calcium to enter the cell. The main cause of non-food borne diarrhoea and food poisoning is this toxin. Cal-pain activation and subsequent cell death are caused by calcium influx, which is dose-dependent.

In sheep, enterotoxaemia and hemorrhagic enteritis are linked to ETX. By destroying tight junctions and the lamina propria, the toxin is triggered by enteric proteases and causes an increase in intestinal permeability. It accumulates in the kidney and brain and induces perivascular edoema with fast cellular swelling, but the mechanism is yet unknown.

The binary toxin known as ITX is made up of the proteins Ia and Ib. Ib joins forces with Ia after attaching to a cell surface receptor. After then, the complex is endocytose. Ia will enter the cytosol via a membrane channel made by Ib and use ADP-ribosylation to depolymerise the actin cytoskeleton.

It has been demonstrated that NetB, a pore-forming toxin found in avian necrotic enteritis, shares 38% of its sequence with CPB. Although it has not been connected to human pathogenicity, its discovery led to the type G classification.

Evaluation

Stool tests, including stool culture and ELISA testing for CPA toxin, should be carried out in cases of suspected C. perfringens infections. WBCs, ova, and parasites are frequently included in stool investigations as well to help rule out alternative causes. Imaging will be necessary in cases of more severe clostridial infections to help locate the afflicted tissue.

In addition to blood tests, which comprise the following: in situations with clostridial myonecrosis, imaging such as an X-ray or computerised tomography (CT) scan of the afflicted area should be acquired.

- Thorough blood count

- Biochemical panel

- Blood testing

- Levels of creatine kinase

- A blood gas analysis

- Acid lactate

Treatment/Management

The majority of acute diarrheic diseases caused by C. perfringens are self-limiting, therefore only supportive care is required to keep a euvolemic state. Typically, antibiotics are not necessary.

Only clostridial sepsis, a medical emergency, is an exception. Because red blood cells are destroyed by CPA, clostridial sepsis frequently manifests as septic shock with potential intravascular ultrasound hemolysis. Early antibiotic therapy with penicillin G plus clindamycin, tetracycline, or metronidazole combined with surgical debridement of necrotic tissue may be used in this circumstance to assist prevent death. Without source control, these patients are likely to be resistant to medical treatment.

A surgical consultation is required if there is a possibility of clostridial myonecrosis. Consultations shouldn't be postponed while awaiting lab or imaging results. Antibiotics with a broad spectrum of activity should be mycobacterial culture given right away. Hyperbaric oxygen has also been proven to enhance outcomes in patients with serious infections.

Diagnosis

Infected acute diarrhoea

- Salmonella Campylobacter Norovirus Staphylococcus aureus

- Abdominal sepsis caused by Escherichia coli generating Shiga toxin

- Appendicitis

- Bacterial colitis

- Hemorrhagic colitis

- Damaged stomach ulcer

- Pancreatitis

- Myonecrosis and clostridial cellulitis

- Klebsiella Streptococcus pyogenes, Escherichia coli,

- Staphylococcus

Anaerobic bacteria : Peptostreptococcus and Bacteroides

Prognosis

Most cases of non-food borne diarrheic illness and food poisoning are self-limiting. Hospitalised patients require fluid resuscitation and, if tolerated, a progressive diet. In general, the outlook is favourable. Contrarily, sepsis and clostridial myonecrosis are medical crises with unreliable prognoses. It is crucial to seek treatment as soon as possible, including surgical debridement. Even with the right care, the mortality rate is between 20 and 30 percent, but when there is no care, the mortality rate is 100 percent.